British Mandate

Whether it is in drama, journalism, or academia, there are always subjective and different ways of examining historical events. A new Channel 4 series The Promise, by Peter Kosminsky, illustrates once again the deception and dishonesty of presenting only one side of a story. The series purports to objectively illustrate how so many British soldiers, seeing at first hand in Europe the result of what the Germans perpetrated against the Jews, came to Palestine to serve in the British Mandate Army, imbued with a pro-Jewish feeling, a sense that the Jews deserved a refuge–but the actions of the wicked Zionists turned them against the Jews and left them feeling completely on the Arab side. So here is another point of view. And if you doubt my objectivity I refer you to Conor Cruise O’Brien’s The Siege for a disinterested perspective.

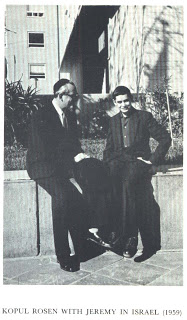

When I first went to Israel as a teenager in 1956, I remember vividly how surprised I was when I encountered so much ill feeling and resentment towards the British Mandate. I was made to feel that being British was an embarrassment.

When I first went to Israel as a teenager in 1956, I remember vividly how surprised I was when I encountered so much ill feeling and resentment towards the British Mandate. I was made to feel that being British was an embarrassment.

It is not as though I did not know about the history of the British Mandate. Britain had captured the Middle East from the Turks in the First World War. The Balfour Declaration had promised a homeland for the Jews in their ancestral lands, but the interests of the Arab population had to be preserved. When Britain was granted the mandate in 1922, the first High Commissioner, Sir Herbert Samuel, a Jew, succeeded in alienating everyone. It was an impossible situation.

The Ottoman Empire had welcomed Jews ever since their expulsion from Spain. However, as anti-Semitism grew in Europe during the late 19th and early 20th centuries and Jewish immigration began to increase, tensions rose. Initially some Arab leaders welcomed the influx and its promise of joint development. Emir Feisal (son of the King of Hejaz) and Chaim Weizmann (later president of the World Zionist Organization) signed an agreement in 1919 to work together to achieve common goals. It was, sadly, short-lived.

Originally the plan was for the whole of Palestine and Transjordan to be divided between Arabs and Jews. But the British began to play the old game of Divide and Rule, hiving off Transjordan and sending army officer Sir John Glubb to establish and train the Arab Legion. The rise of Arab nationalism led to riots, attacks on civilians, and the notorious Hebron massacre of Jews in 1929. The British felt they had to appease the Arabs, so they began to restrict Jewish immigration. The White Paper of 1939 virtually closed the door on Jewish immigration precisely at the moment when a haven might have saved hundreds of thousands from the Nazi barbarity.

Those who did manage escape Europe had to face harsh detention camps in Atlit, and then Cyprus. Refugee ships were sent back to Europe or redirected to Cyprus or Mauritius. The British army and police force became notorious for their harsh and humiliating treatment of Jews. Indeed, the Board of Deputies had evidence that many of the volunteers who went to Palestine had anti-Semitic records. Still, the main Jewish community under Ben Gurion, despite his disgust at British policy, was committed to cooperation with the Mandate forces and participating in the war effort. He famously said, “We will fight the White Paper as if there is no war, and fight the war as if there is no White Paper.” But as diplomacy was not working, extreme Jewish groups such as Etzel (Irgun) and Lehi (Stern Gang) began to initiate campaigns of violence against British military and Arab targets. The first member of a Jewish underground group, Shlomo Ben-Yosef, was executed in 1938, but no further executions of Jews were held in Palestine until after the war when they resumed their campaigns.

In 1945 the Mandate enacted the Defense (Emergency) Regulations which suspended Habeas Corpus, established military courts, and prescribed the death penalty for carrying weapons or ammunition illegally and for membership in illegal organizations. The post-war foreign secretary of the Labour government was the notorious Ernest Bevin, who was adamantly opposed to the idea of a Jewish state. Richard Crossman believed he was profoundly anti-Semitic. He pushed the Mandate authorities to take a very hard line.

In 1946 Michael Eshbal and Yosef Simchon were arrested and sentenced to death. The Irgun began a policy of reprisals. Five days later they kidnapped five British officers in Tel Aviv, and another one the following day in Jerusalem. Two weeks later, when Eshbal’s and Simchon’s sentences were commuted to life imprisonment, the officers were released.

In January 1947, another Irgun militant, Dov Gruner, was sentenced to death. On January 26, two days before Gruner’s scheduled execution, Irgun kidnapped a British intelligence and the president of the district court of Tel Aviv. Sixteen hours before the scheduled execution, the British forces commander announced an “indefinite delay” of the sentence, and Irgun released its hostages.

On April 16, 1947, Gruner and three other militants, Yehiel Dresner, Mordechai Alkahi and Eliezer Kashani, were executed. In May 1947, forty-one prisoners broke out from Acre Prison. Six of them were killed and seven others were rearrested. Among the organizers, Avshalom Haviv, Yaakov Weiss and Meir Nakar were tried by a military court and sentenced to death.

The Irgun retaliated by capturing two British soldiers and announced that if their men were put to death they would do the same to the British soldiers. The High Commissioner Alan Cunningham gave the order and the Irgun men were executed. The day afterwards the bodies of the two British soldiers were discovered hanging from olive trees. The Irgun admitted to the killings.

There were other acts of Jewish terror, but this was the one act that Britain never forgave the Jews for. The British press attacked the Zionists. The Board of Deputies of British Jews issued a full condemnation. So did the Jewish community in Israel. Ben Gurion had been resolutely against violence or terror. Indeed, the Haganah had been working with the British forces to find the captured British soldiers. But the endemic anti-Semitism of much of British society exploded.

It is argued in their defense that the campaigns of the Lehi and Stern Gang contributed as much as anything else to Britain’s giving up on Palestine. She ceded responsibility to the UN, which voted for partition. But the Arabs rejected the compromise and declared war. Behind the scenes Bevin plotted with the Jordanians and also negotiated “the Portsmouth Treaty” with Iraq (signed on January 15, 1948), with the British undertaking to withdraw from Palestine in such a fashion as to provide for swift Arab occupation of all its territory to destroy the Jewish state. As the British withdrew they handed over as much of their hardware as they could to the Arabs. The ill feeling with the Foreign Office has festered to this day, which is why the Queen has never been allowed a formal visit to Israel.

So it may well be that Sabra arrogance and triumphalism alienated British soldiers and policemen working in Palestine. But my goodness me, they and their masters did more than enough to deserve it. Two wrongs do not make a right of course, but there are two sides to every story.